Red Summer

In 1919, white Americans visited awful violence on black Americans. So black Americans decided to fight back.

Photo by Jun Fujita. Courtesy of the Chicago History Museum

(ICHi-65481).

In Longview, Texas, in July 1919, S.L. Jones, who was a teacher and a local distributor of the black newspaper the Chicago Defender, investigated the suspicious death of Lemuel Walters. Walters was a black man who was accused of raping a white woman, jailed, and ultimately found dead under “mysterious” circumstances. When the Defender published a story about Walters’ death, asserting that the alleged rape had been a love affair and Walters’ death the result of a lynching, Jones came under attack, beaten by the woman’s brothers.

Hearing a rumor that Jones was in trouble, Dr. C.P. Davis, a black physician and friend of the teacher, tried to get law enforcement to protect him from further violence. When it became clear that this help was not forthcoming, Davis organized two-dozen black volunteers to guard Jones’ house. That same night, a mob surrounded the dwelling. Four armed white men knocked on the door, then tried to ram it down. The black defenders, who were arranged around Jones’ property, opened fire. A half-hour gun battle ensued, in which several attackers were wounded; the posse retreated.

Hearing the town’s fire bell ringing to summon reinforcements, Jones and

Davis went into hiding, knowing that they wouldn’t be able to defend themselves

against a larger mob. Davis borrowed a soldier’s uniform, put it on, and took

the first of several trains out of the area. At one point, he asked a group of

black soldiers he found in a train car to conceal him in their ranks, which they

did, contributing to

his disguise by giving him an overseas cap

and a gas mask. Later that day, Jones also managed to escape. But their

successful resistance and flight were bittersweet victories: Before the episode

was over, Davis’ and Jones’ homes were burned, along with Davis’ medical

practice and the meeting place of the town’s Negro Business Men’s League. Davis’

father-in-law was killed in the violence.

In his new book, 1919, The Year of Racial Violence: How African Americans

Fought Back, David F. Krugler, professor of history at the University

of Wisconsin–Platteville, looks at the actions of people like Jones and Davis,

who resisted white incursions against the black community through the press, the

courts, and armed defensive action. The year 1919 was a notable one for racial

violence, with major episodes of unrest in Chicago; Washington; and Elaine, Arkansas, and many smaller clashes in both the North

and the South. (James Weldon Johnson, then the field secretary of the NAACP, called this time of violence the “Red Summer.”) White mobs

killed 77 black Americans, including 11 demobilized servicemen (according to the

NAACP’s magazine, the Crisis). The property damage to black businesses

and homes—attacks on which betrayed white anxiety over new levels of black

prosperity and social power—was immense.

The history of black responses to the violence of 1919—which ranged from the

use of a single weapon against a home invader, to the organization of defensive

posses like Davis’ that were meant to protect potential victims of lynching, to

the deployment of groups of men who patrolled city streets during unrest—makes

it clear that armed self-defense, far from being an invention of Malcolm X and

the Black Power movement, is a strategy with deep roots. As we celebrate the

50th anniversary of the civil rights movement, the story of

nonviolence—a beautiful strategy with uncontestable moral force—has taken center

stage. However the story of active self-defense against violence—a tradition

that developed before, and then alongside, nonviolent resistance—is too often

dismissed or simply ignored. Even before slavery had been outlawed, black

Americans took up arms when their lives and livelihoods were threatened. Their

experiences make the familiar history of marches and peaceful protest more

complex. But the story of the civil rights struggle is incomplete without

them.

Why was there a spike in violence in 1919? Krugler argues that black service

members’ experience in World War I was one of the catalysts. In many places,

demobilized black veterans, having fought for their country, had a diminished

tolerance for racial discrimination—and their families, having sacrificed on the

homefront, felt the same way. Meanwhile, white civilians resented what they

perceived as an excess of pride (what an Army captain, registering his concern

with the Military Intelligence Division, called “social aspirations”) in those

who had served. Servicemen were allowed to wear their uniforms for three months

after being “demobbed.” Georgian Wilbur Little was lynched in April 1919,

reportedly for the sin of wearing his after the cutoff date—a crime that

suggests how much the vision of black men in uniform threatened the racial

regime.

The black community’s defensive actions in response to racial violence were

also shaped by the war. Veterans took the initiative in armed self-defense,

using their combat experience and knowledge of tactics and organization. But

communities around them—many of whom had worked for the war effort in civilian

capacities—were also energized by their wartime experiences and by the presence

of the returned service members. (C.P. Davis and S.L. Jones were not veterans,

but they were affected by the prevailing climate nonetheless. Davis’ escape took

advantage of the cover provided by his borrowed uniform and relied on solidarity

from black soldiers who were willing to vouch for him.)

Meanwhile, writers and journalists in the black press—some of whom had

served—turned out prose that was increasingly bold, calling for armament and

self-defense, and shaping the image of what came to be called the New Negro. That year, poet Claude McKay published his

sonnet “If

We Must Die” in the socialist magazine the Liberator:

Though far outnumbered let us show us brave,

And for their thousand blows deal one death-blow!

What though before us lies the open grave?

Like men we’ll face the murderous, cowardly pack,

Pressed to the wall, dying, but fighting back!

Activists followed these calls for resistance with attempts to work within

the legal system to defend those who fought back. After each episode of

violence, the NAACP took new legal initiative in prosecuting white rioters and

representing black people who had acted to defend themselves. Sometimes, as in

the aftermath of the violence in Longview, Texas, NAACP lawyers were able to get

prisoners who had been found with weapons released by arguing that their actions

were taken in self-defense. These legal victories—though somewhat diminished by

the difficulty lawyers had in landing convictions of white rioters—were

nonetheless significant.

While there is a notable cluster of examples of black communities fighting back in the racial conflicts of 1919, the history of armed self-defense goes back even further. Law professor Nicholas Johnson points to fugitive slaves who armed themselves against slave-catchers as some of the earliest examples of the practice. In another dark period of racial violence at the end of the 19th century, Ida B. Wells-Barnett, a journalist and investigator of lynching, advocated “boycott, emigration, and the press” as weapons against white aggression, outlining the rationale in her 1892 pamphlet Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases. When those peaceful strategies failed, Wells-Barnett thought a more active strategy was the answer, observing: “The only times an Afro-American who was assaulted got away has been when he had a gun and used it in self-defense.” For this reason, she wrote, “[A] Winchester rifle should have a place of honor in every black home, and it should be used for that protection which the law refuses to give.”

Some citizens caught up in racial violence at the turn of the 20th

century shared Wells-Barnett’s philosophy. Krugler cites instances of

self-defense in turn-of-the-century racial strife in Wilmington, North Carolina, in 1898; Evansville, Indiana, in 1903; Atlanta in 1906; and Springfield, Illinois, in 1908. In Evansville, Krugler writes,

“[A]pproximately thirty black men assembled to drive away white vigilantes

attempting to break into the county jail to lynch a black prisoner.” In

Springfield, “[B]lack snipers fired on white rioters from a saloon window, and

twelve armed black men formed a patrol and fired on members of a mob leaving the

site of one attack.”

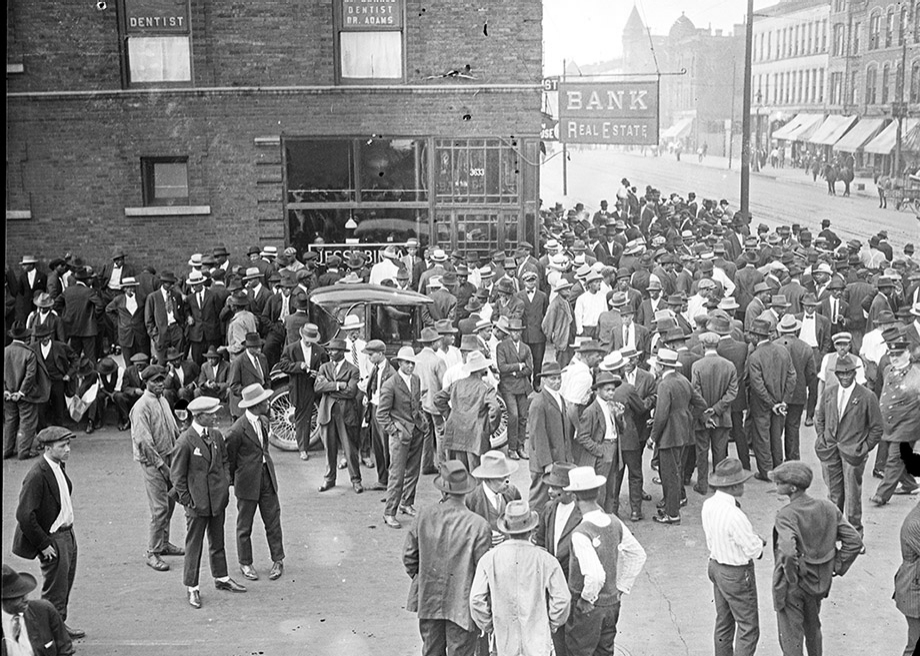

Photo by Jun Fujita. Courtesy of the Chicago History Museum

(ICHi-65495).

In his research on the unrest of 1919, Krugler found evidence of self-defense

that was both highly coordinated and ad hoc. “In Chicago,” he told me, “we have

examples of individual stockyard workers who go to work, are attacked, and turn

and fight. That’s not premeditated; that’s a human response to a

life-threatening danger and risk—but it still counts as self-defense.” Also

during the unrest in Chicago, “The veterans of the 8th Regiment put on their uniforms, found weapons,

and took to the streets to try to stop the mob violence”—a preplanned action

that took advantage of their military training and status in the

community.

One of the problems with writing a history of armed self-defense during

episodes of racial violence lies in establishing what actually happened. The

events are obscured by the motivations of the authors of many of the historical

sources, as well as the simple fog of war—these conflicts were complex events

unfolding, in some cases, over many city blocks. Krugler triangulates between

sources, looking at black and white newspapers, records of the tribunals held

after some of the riots, and the reports of investigators from the Military

Intelligence Division and the Bureau of Investigation (as the

FBI was called in its first two decades of operation).

Comparing-and-contrasting these sources, as Krugler does in a section on the

Chicago unrest called “The Fictional Riot,” shows how self-defense could look

very different depending on the point of view of the witness. The soldiers from

the 8th Regiment, who, black onlookers reported, instilled a sense of

calm in the community merely by their presence, showed up very differently in

the Chicago Daily News’ coverage. One detachment of veterans was

described as “a group of twelve discharged negro soldiers, all armed,” who had

“terrorized small groups of whites in various parts of the south side all

afternoon.” The Herald-Examiner reported that several thousand

decommissioned members of the 8th Regiment had stormed the regiment’s armory,

wounding more than 50 people as they seized weapons. “Black Chicagoans, menaced

by gangs and mistreated by the police, now [confronted] a white-written

narrative about the riot that cast them as the wrongdoers,” Krugler writes. This

was one of the drawbacks of self-defense, which, in a racist society, put those

who resisted in perilous positions, vulnerable to further violence and legal

prosecution.

Americans have wholeheartedly adopted the history of nonviolent protest as

part of our national mythology. But we’re hesitant to commemorate the history of

black self-defense. As historian Peniel E. Joseph writes, radical strains of resistance during the 1950s, 1960s,

and 1970s—the activism of Malcolm X and the Black Power movement—are often

remembered as “politically naïve, largely ineffectual, and ultimately

stillborn.” Yet, Joseph (and a host of

other historians who have looked anew at Black Power and related activism in

the past decade or so) argues that the activists who believed in Black Power

precepts of armed self-defense and radical self-determination were always a part

of the civil rights movement, acting alongside people who believed in

nonviolence. Joseph and other scholars of Black Power look at civil rights and

Black Power as “part of the same historical family tree.”

Perhaps our eagerness to dismiss self-defense stems from the fact that it

makes us confront uncomfortable questions about our present-day realities. The

history of armed black self-defense is a story of individual resistance in the

face of unfairness and of successful community organization in places where the

dominant culture refused protection. Like the history of nonviolence, it’s a

stirring story, reminding us of the real dangers black people faced and of their

refusal to submit, despite the prospect of reprisal and the possibility of legal

consequences. But given the fact that black Americans still face

life-threatening violence at a disproportionate rate, and that some of this

violence—now, as in years past—comes from officials sworn to protect and serve, the history

of armed self-defense is less readily adaptable for anodyne commemorative

purposes.

Still, this other aspect of civil rights history can be found even in the

more traditional narratives, once you start to look. I asked Krugler to comment

on the relationship between the history of self-defense and the dominant story

of civil rights. He pointed to a recent article in the Washington Post about the

unveiling of the Rosa Parks papers collection at the Library of Congress. The

author, Michael E.

Ruane, began the piece by referring to one of Parks’ childhood memories. Parks remembered staying up late with her grandfather as a young girl in rural Alabama, as he sat with a shotgun and guarded against possible attacks from the members of the Ku Klux Klan. “Even someone who’s a mainstay of the nonviolent part of the civil rights movement grew up understanding the importance of armed self-defense against racial terrorism,” Krugler pointed out. Rosa Parks was 6 years old in 1919.

Ruane, began the piece by referring to one of Parks’ childhood memories. Parks remembered staying up late with her grandfather as a young girl in rural Alabama, as he sat with a shotgun and guarded against possible attacks from the members of the Ku Klux Klan. “Even someone who’s a mainstay of the nonviolent part of the civil rights movement grew up understanding the importance of armed self-defense against racial terrorism,” Krugler pointed out. Rosa Parks was 6 years old in 1919.

Comments

Post a Comment